Former Vietnam prisoner of war Paul Galanti recalls internment

RICHMOND, Va. (WRIC) -- Paul Galanti, a former prisoner of war from the Vietnam War, sat down with 8News Chief Meteorologist Matt DiNardo at the Virginia War Memorial to share memories of the 2,432 days he spent in internment.

Galanti carries numerous accolades including two Legions of Merit for combat, the notorious service medal, a Bronze Star Medal for combat, 9 Air Medals, the Navy Commendation for medal for combat and two Purple Hearts. He is also a Silver Star recipient.

DiNardo opened the conversation by discussing the lack of rules when it came to Galanti's treatment as a prisoner of war. However, Galanti said he was somewhat prepared for it.

Galanti attended Navy survival school in Warner Springs, California.

A photo of young Paul Galanti in the Navy (Courtesy of Jamie Galanti)

"You train for it, but you can't really train for it because the thing that gets to you most when you're in a POW camp [is] you don't know when it's going to be over," Galanti said.

Galanti touted the successes of his fellow pilots right away, saying they were "flying jets off aircraft carriers that had a fatality rate that equals combat in peace time."

Galanti graduated from the Naval Academy in 1962. He became a flight instructor in Pensacola, Florida until 1963. He was assigned to the USS Hancock in 1964. Just a year after that, Galanti was headed to Southwest Asia as the Vietnam conflict was about to begin.

Galanti flew a Douglas A-4 Skyhawk.

"I was a good pilot," said Galanti. "I was never 100% sure I'd be alive at the end of a night carrier approach."

"The A-4 is a tiny airplane," said Galanti. "I described it as a 34 regular fit."

The runway on the USS Hancock is 888 feet according to the USS Hancock Association. Compare that to Richmond International Airport, with its longest runway being 9,003 feet.

Galanti said the USS Hancock was built during World War II to land Grumman F6F Hellcat planes, which landed at 80 miles per hour. Meanwhile, the Skyhawk landed at 135 miles per hour on the same ship.

Pilots had to maneuver their landings around two small white lights in the middle of the ocean. Galanti said the experience was extremely rewarding.

"Combat was a piece of cake compared to the landing," Galanti said.

Galanti flew 96 and a half missions. The half references the mission with no landing. After bombing railroad cars, Galanti's plane was taking on fire and he ended up having no choice but to eject.

The first thing Galanti noticed was a "wap" sound behind his head. Then, the power shut off on his plane, the dashboard only showed error messages.

"All of the sudden the engine starts vibrating and a I heard this wrapping sound as little blades are coming off the engine," Galanti said. "I said, 'I hope I hit the water.' The water was safety."

Galanti said he pulled down a face curtain to prevent getting hit by a blast of air when ejecting from the plane. He spent 30 seconds in the parachute before landing in Vietnamese territory.

Galanti said he carried a pistol with six rounds in it. If he ended up in this position, he said he would use five rounds on the enemies and one for himself, "because they're not taking me."

"The one who got there first was probably 12 years old, and he had a rifle and he's shaking like a leaf -- and I didn't want to rattle him," Galanti said.

Galanti was captured on June 17, 1966.

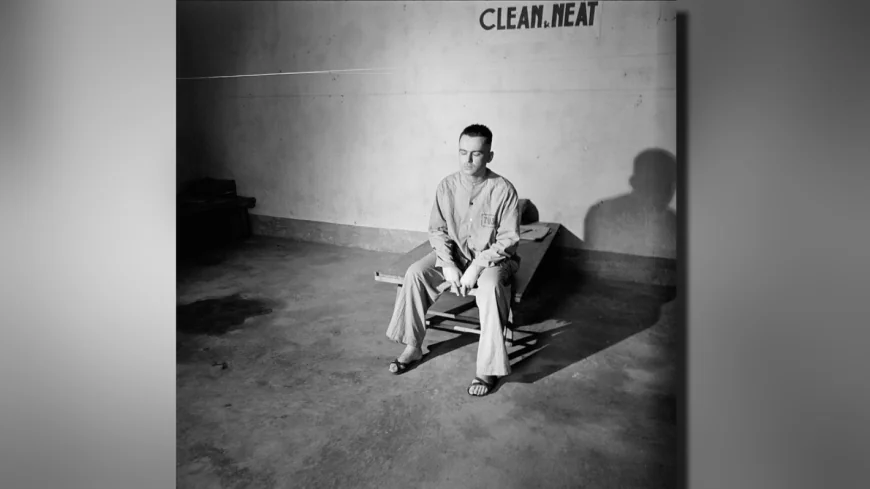

Galanti in the POW camp (Courtesy of Jamie Galanti)

It took 12 days walking barefoot, wearing nothing but underwear for 100 miles to get to Hanoi where the POW camp was. Galanti said they would parade the prisoners through every village and get the crowd fired up to throw things.

"I was lucky to arrive in Hanoi the first day we bombed Hanoi," Galanti said sarcastically.

Galanti said this time period passed by quickly because he was undergoing "interrogation," referencing being beaten by Vietnamese officers four times per day.

Military members communicated in solitary confinement through a tap code using a five by five tic tac toe board. They didn't tap through morse code because tapping a dash sounds too similar to tapping a dot.

An example of the tic tac toe board

Each tap corresponded to where the letter was on the board. For instance, to use the letter A, one would tap twice, once for the top row and once for the furthest left column.

"I don't think I was anywhere in Hanoi, even in solitary confinement, where I didn't know everybody in the camp within 10 or 15 minutes of arriving there," Galanti said. "That was our one thing that made us feel food, was we were putting this over on these guys and they could never get it out of us."

Galanti said people were writing books and sharing jokes using the tap codes heard through the walls.

Once prisoners were released from solitary confinement, Galanti said they used hand motions to communicate.

"They couldn't get us down. It was tough and you had to act, sort of, recalcitrant," Galanti said.

Shortly after Galanti was shot down in 1966, the Navy sent a representative to inform his wife, Phyllis Galanti, what had happened. This news seemingly flipped a switch for Phyllis, according to Galanti. The woman who was once reserved and quiet, soon became a national advocate to bring prisoners of war home.

Paul and Phyllis (Photo: Jamie Galanti)

Paul and Phyllis (Photo: Jamie Galanti)

Paul and Phyllis (Photo: Jamie Galanti)

Paul and Phyllis (Photo: Jamie Galanti)

"She was very shy, painfully shy," Galanti said. "In college she was a French major but she was so shy, she was afraid to get up in front of a class of kids and teach them French."

When Galanti returned home, he was shocked to learn his wife had given thousands of talks across the country.

"I came home married to one of the most famous women in the United States," Galanti said.

Phyllis served as president of the National League of Families, which encouraged women to speak up and fight for reunification with their husbands.

Seven years in captivity not only changed Paul, but it changed Phyllis too.

February 12, 1973 is the day that Galanti was freed from the camp. He got on a series of planes and landed on February 15, missing Valentine's Day by a couple of hours.

Galanti said their senior officers ordered them to show no emotion upon release so it couldn't be reframed positively for propaganda purposes.

"The weirdest thing about the prisoner exchange, nobody's smiling. Nothing," Galanti said. "They got absolutely no film out of that."

Galanti said the prisoners of war knew everything about each other except what they looked like. Upon release, they walked around looking at nametags to match faces up to names.

"That evolved into probably the most gung ho military group ever. Whenever we got together, we had more fun than anybody in the history of the world," Galanti said.

Both Paul and Phyllis became known for pioneering programs to help veterans and former prisoners of war locally and nationwide.

The full interview between Matt DiNardo and Paul Galanti can be viewed on WRIC+.

VENN

VENN